By Anna Radar

The Long and Weary Road: Addressing Sleep Needs in Substance Abuse Recovery

Overview

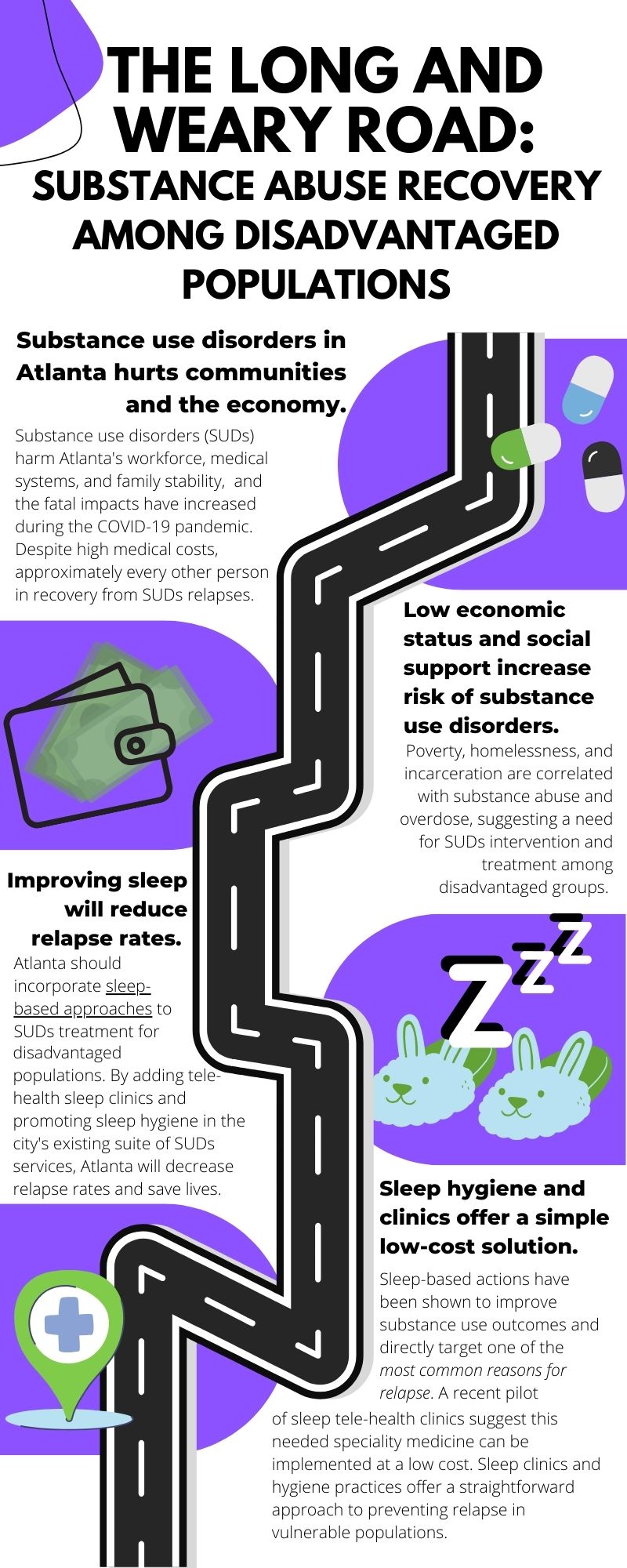

Substance use disorders (SUDs) undermine Atlanta’s communities, workforce, and economy through the high rates of relapse, costs of treatment, and increasing fatality rate. Individuals lacking social or economic support face an increased risk of developing SUDs, and nearly one-third of the unhoused population struggle with a SUD. Although Atlanta has several policies and programs in place to preempt and treat substance abuse, relapse continues to bring substance abuse to the forefront of the Atlanta metro area. Given that relapse occurs in approximately half of individuals in SUDs recovery, the prevention of relapse marks a critical area for supporting healthy long-term outcomes. Other state and local governments have addressed the issue of relapse through significant remodeling of their social infrastructure such as Medicaid expansion, carceral system reform, and “Housing First” harm reduction approaches. However, Atlanta’s current social infrastructure and its position within Georgia’s political scene call for more innovative options that require less groundwork. Previous work in neuroscience and social sciences suggests that issues with sleep pose a significant barrier to recovering and remaining in recovery from SUDs. Disordered sleep or other sleep issues have been identified as a common comorbidity with SUDs and are often cited as a reason for relapse. Thus, policymakers can use novel sleep-based interventions to generate improved outcomes and prevent relapse at low costs through telehealth sleep clinics and the application of sleep hygiene techniques to treatment programs.

Substance use disorders in Atlanta

Substance abuse and addiction are commonly recognized issues that heavily impact the Atlanta metro area, with 8.3% of the population over 12 years old – 350,000 people – diagnosed with substance use disorders (SUDs).1 Experts have suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased risk of negative health outcomes for individuals with SUDs due to both physical health challenges of COVID-19 (e.g., reduced respiratory function) as well as social isolation and stigma (e.g., lack of bystanders to administer naloxone during overdose).2 From 2019 to 2020, deaths due to unintentional drug overdose increased by 41% in Georgia, with even larger increases among essential workers and unemployed populations.3 Substance abuse decreases labor force participation while increasing medical costs; annual medical costs due to substance use disorders are estimated at ~$13.2 billion nationwide.4, 5 Moreover, the effects of substance abuse reverberate throughout the community, impacting family and neighborhood stability, educational outcomes, and the incarceration system.

Drug relapse is estimated to occur in 40–60% of individuals treated for substance abuse within a year of treatment.6 Of reported deaths due to unintentional drug overdose, 10.1% had previously been treated for substance abuse, and 7.3% had relapsed.3 Notably for policy interventions, some groups are particularly at risk for drug relapse; low socioeconomic status (SES) and low levels of social support are two of the strongest predictors of drug relapse.6 In addition to the previously noted incarcerated population, unhoused individuals are disproportionately likely to have a substance use disorder: 32% of unhoused individuals surveyed in Atlanta live with a substance use disorder.7 At the national level, individuals in under-resourced urban neighborhoods have higher rates of opioid and heroin overdose than their high SES counterparts, and unhoused individuals have even higher rates of opioid overdose than their low SES housed counterparts.8, 9 The combination of increased overdose deaths in recent years, the high rate of relapse, and the fatality of relapse suggests that issues related to substance abuse must be addressed urgently and strategically to reduce community and economic impacts of SUDs, particularly among populations at high risk due to houselessness, low socioeconomic status, or a weak social safety net.

How can policy address this?

Past policies in Atlanta

In Atlanta, several new policies addressing SUDs have been implemented in recent years at the local, state, and federal levels. Current policies touch on several factors contributing to SUDs and work to curb substance abuse through healthcare access, housing support, and education. At the federal level, the SUPPORT Act was passed in 2018 to improve access and options for SUD treatments through Medicaid, including medication-assisted treatment.10 In Georgia, 2022 was deemed the Year of Mental Health, and several new pieces of state legislation were passed that improved access to healthcare for SUDs.11 The crown jewel of these bills, the Mental Health Parity Act, was passed in July 2022 and requires insurance companies to cover mental health in a manner equivalent to physical health. While this is a critical step for those in recovery, advocates saliently note that insurance rarely covers inpatient rehabilitation, medical detox, continuous counseling, or a sober living environment – crucial components of a strong recovery regimen.12 At the county level, an Opioid Coordinator position was created in Fulton County to coordinate efforts between community organizations and bureaucratic officials.13 Moreover, in 2017, Fulton County launched the first lawsuit against companies linked to the opioid crisis, which was eventually subsumed under the state’s case.14 In 2022, Georgia won $636 million from the settlement with these companies, although these funds remained to be allocated by the Georgia Opioid Settlement Advisory Committee, which is still in the early stages of formation and will comprise appointees by state and local governments.15, 16

Most directly tied to SUDs recovery, the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities (DBHDD) offers outpatient care to those with SUDs.17 Homing in on high-risk groups such as unhoused or low SES populations, the Georgia DBHDD also implements the Georgia Housing Voucher Program (GHVP), a Housing First-style approach which provides individuals with permanent supportive housing to foster long-term recovery. Additionally, the Bridge Funding program offers these individuals financial assistance for start-up expenses.18 To be eligible for these programs, an individual must have a “Serious and Persistent Mental Illness” (including SUDs) and either previous state hospitalizations, incarceration, or periods of houselessness.18 However, the efficacy of these initiatives is hindered by legal, structural, and economic barriers that remain in place. Specifically, criminalization of drug use, poor healthcare coverage (in part due to the lack of Medicaid expansion in Georgia) and high costs of medical care contribute to the shortcomings of these housing programs.19 Moreover, a lack of affordable housing severely diminishes the reach of the GHVP initiative and other housing programs; this affordable housing crisis has been detailed by Dr. Dan Immergluck as a product of Atlanta’s political partnerships with private corporations (see Red Hot City: Housing, Race, and Exclusion in Twenty-First Century Atlanta for more).4 While the current policies in place in Atlanta begin to address social determinants of SUDs recovery, further action is needed to address the sprawling impact of SUDs. Future short-term policy action must both i) work within Atlanta’s current social infrastructure without extensive additional costs and ii) consider the specific needs and circumstances of those recovering from SUDs, including the protection of their agency and dignity.

Innovative policies beyond Atlanta

In other states, important state-level policies have been introduced to lower the legal, structural, and economic barriers to SUD recovery. Medicaid expansion, which has not been implemented in Georgia, would offer healthcare to the 25% of uninsured adults in Georgia living with a substance abuse or mental health disorder and provide funding for more behavioral health services.21 In West Virginia, the adoption of Medicaid expansion reduced the proportion of uninsured substance abuse and mental health-related hospitalizations from 23% to 5% in its first year, suggesting that Medicaid expansion may reduce the economic burden of SUDs as well.22 While Medicaid expansion requires action at the state level, this policy solution provides important insights regarding the impact of medical care access on patient outcomes.

A more flexibly applied policy solution by California Governor Gavin Newsom focuses on streamlining resources into behavioral health treatment plans for those most vulnerable to neglect by current social policies.23 Set to begin this Fall, the Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment (CARE) Court proposal will target “the most severely impaired” individuals and aims to meet the mental health and basic needs of these individuals prior to incarceration or houselessness.24, 25 The CARE Court works within the community (as opposed to within institutions) to provide individualized plans of social services, behavioral healthcare, legal support, and other interventions to those with severe mental illness. However, the $14 billion state-wide investment in this project presents a challenge to scaling this solution down to the local level and requires more substantive infrastructure than is in place currently in Atlanta.23 Moreover, despite the CARE Court’s self-determination focus, critics of this policy underscore the dangers of over-policing minoritized groups and the likely increase in the number of conservatorships, which may drive outcomes towards a more extreme form of policing.26 The proposed use of involuntary court-ordered treatment by this program further removes agency from individuals and is strongly opposed by Disability Rights California.27 Future data from the CARE Court initiative will highlight the most effective components of this comprehensive program as well as its pitfalls to inform behavioral health policies across other parts of the country.

While Medicaid expansion and individualized interventions may offer effective tools to for addressing SUDs, both require infrastructure beyond the local level and available funds. Although these offer potential policy targets in the long-term, here we identify a more appropriate and immediate target for local policy.

What about sleep-centered policy options?

Atlanta’s Housing-First programming (i.e., the GHVP) offers an important first step in addressing social determinants of substance abuse recovery. As noted, the lack of affordable housing thwarts the full potential of this programming and necessitates further support for those experiencing or in recovery from SUDs. Sleep offers a possible target for policy solutions aimed at supporting substance abuse recovery. The role of sleep in the addiction cycle has been consistently observed across drug types during dependence and recovery, offering a potential point of low-cost intervention. The bidirectional relationship between sleep and addiction includes worse sleep quality following chronic drug use, increased likelihood of relapse following sleep deficits, and general cognitive deficits linked to drug use via poor sleep.28 Among individuals treated for drug dependence, sleep disturbance is cited as one of the most common reasons for relapse.29 In line with these data, researchers have suggested that the failure of current therapeutic options to address this sleep deficit may hinder recovery for many people.28 The National Institutes of Health’s initiative to end addiction explicitly aims to incorporate facets of sleep into new therapies for SUDs.28, 30 Moreover, a network of clinicians considering healthcare for unhoused populations recommends that these populations have access to a sleep specialist, even if only for a diagnosis.31 While treatment of disordered sleep provides an important avenue of intervention for substance abuse relapse, this approach has been largely hindered by the prohibitive costs of sleep studies and sleep medicine specialists.

While policy solutions to address this gap in recovery are sparse, a germane pilot program indicates positive preliminary evidence for a cost-effective way to target sleep in disadvantaged populations during SUDs recovery. In Nashville, a primary care clinic serving the uninsured population developed a low-cost specialty sleep clinic through formulaic screening, telehealth appointments, and supervision from a sleep medicine specialist.32 Prior to this program, the associated primary care clinic, on average, diagnosed and treated one individual per year for sleep issues (i.e., sleep apnea). Following the implementation of the sleep clinic, 18 evaluations were completed over two years, with follow-up tests and treatments provided as needed.32 While this does not capture substance use outcomes, this low-cost model suggests a promising path for treating sleep problems that impede SUD recovery.

Another sleep-based intervention comes from research on sleep quality among an unhoused sample.33 Based on their findings of low-quality sleep among unhoused people, the authors recommend a Sleep First focus, which prioritizes high-quality sleep before other interventions for people experiencing houselessness. This therapeutic approach emphasizes simple sleep hygiene measures such as earplugs and eye masks, evening meditations, and a regular sleep schedule. This approach has been applied in conjunction with typical treatments in an inpatient treatment setting for substance abuse and mental health.34 Participants demonstrated reduced substance abuse behaviors and improved mental health one month after discharge, providing empirical evidence for sleep hygiene interventions. These practices can be incorporated by the Georgia DBHDD into their outpatient and housing-based services or promoted in at-risk groups or those in recovery.33

Policy Recommendations and Actions

To support substance abuse recovery most efficiently among underserved populations in the present state of Atlanta, policymakers ought to integrate these two sleep-based interventions (low-cost telehealth sleep medicine and Sleep First sleep hygiene) into pre-existing services for constituents struggling with substance abuse. Telehealth sleep medicine will be essential for treating sleep disorders common to individuals in recovery, including insomnia, which is reported in two-thirds of SUDs recovery cases, alongside circadian rhythm disorders and sleep-related breathing disorders (e.g., sleep apnea).35, 36 Even if treatment remains inaccessible in some cases, diagnoses can help with disability applications or other social services, offering an entry point for support services. Atlanta’s city governance should partner with local medical schools such as Emory University School of Medicine or Morehouse School of Medicine to lay the groundwork for a telehealth sleep clinic. Through a small grant or incentivized contract, this clinic should be integrated with other SUD resources in metro Atlanta for easy referral, and if proven successful, this program could readily scale to include more clinics across the city. To reach beyond pre-existing services, this sleep clinic may partner with non-profit organizations (e.g., Intown Cares, PAD Atlanta) involved in street outreach to connect potential clients to these services. Moreover, the initial funding for this program could come from the money Georgia recently received in the opioid settlement (see: Past Policies in Atlanta above), and, once established, grants from private or federal sources (e.g., American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). To address general sleep health outside of sleep disorders, the Sleep First approach ought to promote sleep hygiene in both institutional or shelter settings and in outpatient facilities. This programming can build on empirically based recommendations such as enhanced privacy, decreased/white noise during sleeping hours, regular sleep schedules, and mindfulness or meditative practices.33 In conjunction with the sleep clinic to treat sleep disorders, this Sleep First method will address a highly cited reason for relapse: sleep disturbance.

While this policy action is newer than other policy alternatives, the low cost of implementation and high success rate of previous interventions uphold the strength of this policy action. Nonetheless, outcomes must be evaluated for efficacy, particularly regarding substance use outcomes following sleep clinic visits. These evaluations may be delegated to the host universities also serving as research institutions.

Due to the current limitations in Atlanta’s social infrastructure and the state’s tense partisan climate surrounding Medicaid, the addition of sleep clinics and Sleep First practices is the most feasible and cost-effective policy action to improve SUDs outcomes. When the basic need to sleep is met, individuals are more capable of addressing higher-order needs such as employment or taking on the taxing demands of remaining in recovery from SUDs. While it will not eliminate substance abuse alone, this policy intervention provides the appropriate action for the current state of Atlanta while policy for affordable housing and healthcare is shaped in the long term. Through its low costs and relatively easy implementation, sleep-based interventions will target foundational issues upon which to build other structural interventions.

References

- “Substance Use and Mental Disorders in the Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta MSA.” Metro Report. Substance Use and Mental Disorders in Metropolitan Areas: Results From the 2005-2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, May 13, 2014.

- Volkow, Nora D. “Collision of the COVID-19 and Addiction Epidemics.” Annals of Internal Medicine 173, no. 1 (July 7, 2020): 61–62. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1212.

- “Characteristics of Unintentional Drug Overdose Deaths Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Drug Surveillance Unit Epidemiology Section Division of Health Protection Georgia Department of Public Health, n.d.

- Peterson, Cora, Mengyao Li, Likang Xu, Christina A. Mikosz, and Feijun Luo. “Assessment of Annual Cost of Substance Use Disorder in US Hospitals.” JAMA Network Open 4, no. 3 (March 5, 2021): e210242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0242.

- Greenwood, Jeremy, Nezih Guner, and Karen Kopecky. “Did Substance Abuse during the Pandemic Reduce Labor Force Participation?” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Policy Hub, no. 2022–5 (2022). https://doi.org/10.29338/ph2022-5.

- McLellan, A. Thomas, David C. Lewis, Charles P. O’Brien, and Herbert D. Kleber. “Drug Dependence, a Chronic Medical Illness: Implications for Treatment, Insurance, and Outcomes Evaluation.” JAMA 284, no. 13 (October 4, 2000): 1689–95.

- “2022 Point-in-Time Count, City of Atlanta, GA.” Point-in-Time Count. Partners for HOME, 2022.

- Yamamoto, Ayae, Jack Needleman, Lillian Gelberg, Gerald Kominski, Steven Shoptaw, and Yusuke Tsugawa. “Association between Homelessness and Opioid Overdose and Opioid-Related Hospital Admissions/Emergency Department Visits.” Social Science & Medicine 242 (December 2019): 112585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112585.

- Pear, Veronica A., William R. Ponicki, Andrew Gaidus, Katherine M. Keyes, Silvia S. Martins, David S. Fink, Ariadne Rivera-Aguirre, Paul J. Gruenewald, and Magdalena Cerdá. “Urban-Rural Variation in the Socioeconomic Determinants of Opioid Overdose.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 195 (February 2019): 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.11.024.

- “Implementation of the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention That Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act of 2018: Dispensing and Administering Controlled Substances for Medication-Assisted Treatment.” Federal Register, November 2, 2020.

- Byrd, Eve H. “With New Law, 2022 Is the Year for Mental Health in Georgia.” Carter Center. Real Lives, Real Change (blog), April 7, 2022. https://www.cartercenter.org/news/features/blogs/2022/with-new-law-2022-is-the-year-for-mental-health-in-georgia.html.

- Eldridge, Ellen. “It’s the Most Important Part of Addiction Recovery — and Often the Most Difficult to Access.” GPB News, August 4, 2022. https://www.gpb.org/news/2022/08/04/its-the-most-important-part-of-addiction-recovery-and-often-the-most-difficult

- Godwin, Becca J G. “Fulton County Creates New Opioid Coordinator Position.” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 1, 2018. https://www.ajc.com/news/local/fulton-county-creates-new-opioid-coordinator-position/YvZ4Xw1CZ7WfsXBidnUo8O/.

- Capelouto, Susanna and Miranda Hawkins. “Fulton Becomes First Ga. County to Sue Over Opioids.” WABE, October 23, 2017. https://www.wabe.org/fulton-county-sue-drug-companies-opioid-distribution/

- Eldridge, Ellen. “Georgia’s Getting Millions in a Vast Opioid Settlement. But Lack of Transparency Concerns Advocates.” GPB News, November 4, 2022. https://www.gpb.org/news/2022/11/04/georgias-getting-millions-in-vast-opioid-settlement-lack-of-transparency-concerns.

- “Opioid Settlement Agreements.” Governor’s Office of Planning and Budget, n.d. https://opb.georgia.gov/ohsc/opioid-settlement-agreements

- “Substance Abuse Services for Adults.” Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, n.d. https://dbhdd.georgia.gov/be-supported/help-substance-abuse/substance-abuse-services-adults.

- “Adult Mental Health Housing Services.” Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, n.d. https://dbhdd.georgia.gov/be-dbhdd/be-supported/mental-health-adults/adult-mental-health-housing-services.

- Harker, Laura. “Fight Substance Abuse, Improve Mental Health Care to Help More Georgians.” Georgia Budget & Policy Institute, December 13, 2017.

- Immergluck, Dan. Red Hot City: Housing, Race, and Exclusion in Twenty-First Century Atlanta. University of California Press, 2022. 978-0-520-38763-8.

- Dey, Judith, Emily Rosenoff, Kristina West, Ali Mir, Sean Lynch, Chandler McClellan, Ryan Mutter, Lisa Patton, Judith Teich, and Albert Woodward. “Benefits of Medicaid Expansion for Behavioral Health.” ASPE Issue Brief. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, March 28, 2016.

- “Continuing Progress on the Opioid Epidemic: The Role of the Affordable Care Act.” ASPE Issue Brief, Department of Human Health and Services, January 11, 2017.

- Office of Governor Gavin Newsom. “Governor Newsom Launches New Plan to Help Californians Struggling with Mental Health Challenges, Homelessness,” March 3, 2022. https://www.gov.ca.gov/2022/03/03/governor-newsom-launches-new-plan-to-help-californians-struggling-with-mental-health-challenges-homelessness/.

- “Community Assistance, Recovery & Empowerment Act.” California Health and Human Services, n.d. https://www.chhs.ca.gov/care-act/.

- Curwen, Thomas. “‘Deep in the weeds’: California counties face unknowns in launching mental illness court.” Los Angeles Times, May 21, 2023.

- Tobias, Manuela, and Jocelyn Wiener. “California Lawmakers Approved CARE Court. What Comes Next?” Cal Matters, September 14, 2022. https://calmatters.org/housing/2022/09/california-lawmakers-approved-care-court-what-comes-next/.

- “SB 1338 (Umberg) – Disability Rights California Information on CARE Act.” Disability Rights California, February 7, 2023. https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/latest-news/sb-1338-umberg-disability-rights-california-information-on-care-act

- Valentino, Rita J., and Nora D. Volkow. “Drugs, Sleep, and the Addicted Brain.” Neuropsychopharmacology 45, no. 1 (January 2020): 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0465-x.

- Kadam, Maithili, Ankita Sinha, Swateja Nimkar, Yusuf Matcheswalla, and Avinash De Sousa. “A Comparative Study of Factors Associated with Relapse in Alcohol Dependence and Opioid Dependence.” Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 39, no. 5 (September 2017): 627–33. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_356_17.

- “NIH HEAL Initiative Research Plan.” National Institutes of Health, n.d. https://heal.nih.gov/about/research-plan.

- “Sufficient Sleep: A Necessity, Not A Luxury.” HCH Clinicians’ Network, Healing Hands, 18, no. 2 (2014).

- Henry, Olivia, Alexandra Brito, Marguerite Cooper Lloyd, Robert Miller, Eleanor Weaver, and Raghu Upender. “A Model for Sleep Apnea Management in Underserved Patient Populations.” Journal of Primary Care & Community Health 13 (January 2022): 215013192110689. https://doi.org/10.1177/21501319211068969.

- Gonzalez, Ariana, and Quinn Tyminski. “Sleep Deprivation in an American Homeless Population.” Sleep Health6, no. 4 (August 2020): 489–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2020.01.002.

- Morse, Siobhan A., Samuel A. MacMaster, Vicki Kodad, and Kathy Robledo. “The Impact of a Sleep Hygiene Intervention on Residents of a Private Residential Facility for Individuals With Co-Occurring Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders: Results of a Pilot Study.” Journal of Addictions Nursing 25, no. 4 (October 2014): 204–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAN.0000000000000050.

- Chakravorty, Subhajit, Ryan G. Vandrey, Sean He, and Michael D. Stein. “Sleep Management Among Patients with Substance Use Disorders.” Medical Clinics of North America 102, no. 4 (July 2018): 733–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.02.012.

- Grau-López, Lara, Laia Grau-López, Constanza Daigre, Raúl Felipe Palma-Álvarez, Nieves Martínez-Luna, Elena Ros-Cucurull, Jose Antonio Ramos-Quiroga, and Carlos Roncero. “Insomnia Symptoms in Patients With Substance Use Disorders During Detoxification and Associated Clinical Features.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 11 (November 17, 2020): 540022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.540022.